|

Published: 14 September 2010

Australian bamboo takes a stand

Edible shoots and timber are just two of the most recognised uses of bamboo, a plant of economic, social and cultural significance throughout Asia. However, this fast-growing perennial member of the grass family also has a wide range of environmental applications, including carbon sequestration, wastewater reuse, and soil and water erosion control. Australian scientists and environmental engineers are beginning to take another look at this prolific perennial.

In South-East Asia, where bamboo is used primarily as a building material for low-cost structures, it is mostly harvested from wild stands. In other parts of the world, the area under plantation has been increasing at a fast rate; India and China dominate, with approximately 9 million and 5 million hectares respectively.1 In China, the growth in bamboo plantations has been partly driven by fast-growing domestic demand for wood: the country’s need for wood is expected to reach 260 million cubic metres in 2020, with an expected domestic production of only 139 million cubic metres.2 But, demand has also arisen for bamboo construction products from outside China.

|

|

Bambusa arnhemica in flower, Northern Territory. This species is native to Australia. Credit: Donald Franklin.

|

Professor David Midmore, of Central Queensland University, has been involved in an Australian government-funded aid project that investigated silvicultural management of bamboo for shoots and timber in the Philippines and Australia.

Says Professor Midmore, ‘Bamboo growth rates are significantly faster than most woody species soon after planting and for this reason bamboo can be harvested much earlier than forest species. It can produce harvestable culms within 4–7 years of planting, which can subsequently be harvested annually for timber.’

In Australia, initial interest in bamboo in the 80s and 90s as a commercial crop had resulted in 200 hectares under plantation by 2002. However, Mr Bob Gretton, President of the Bamboo Society of Australia, explains that development of an Australian industry has struggled to compete with competitively priced imports, mostly from China.

|

|

Bambusa arnhemica seedlings (at bottom of photo), Otto Creek, Northern Territory. Credit: Donald Franklin

|

‘In the late 1990s Australian bamboo growers planted commercial areas of Dendrocalmus asper, Bambusa oldhamii, Dendrocalamus latiflorus and a couple of other species for shoots,’ he says. ‘However, shoots are being imported at about anything between $2.50 and $4.50 a kilo and it is hard for Australian producers to compete.’

A small number of growers have found niche markets in the supply of fresh shoots to the restaurant market. Hans Erken, who runs a business called Earthcare, is an example. He sends the fresh shoots in the early season straight down to restaurants in Sydney.

Competitively priced imports have also hampered Australian growers interested in supplying bamboo for timber. Other barriers to commercialisation include high labour costs.

|

|

Bambusa arnhemica, shoot. Credit: Donald Franklin

|

‘There are some aspects of bamboo growing that are less like a plantation and more like a horticulture project, so that increases the cost, as against a tree plantation’, says Mr Gretton.

Bamboos require summer water, and (edible) shoot production has a high water demand. This poses problems when water supply is affected by dry conditions. Professor Midmore and Mr Mark Traynor, of the Northern Territory Department of Primary Industries, investigated the ability of bamboo to continue to produce biomass under dry conditions, trialling practices designed to capitalise on this feature.3 They identified management strategies with the potential to allow for both shoot and culm production under seasonally dry conditions, including strategic irrigation and thinning regimes. Factors found to affect shoot and culm yields included the number of culms of different ages in each stand and the age of culms at harvesting.

Professor Midmore and other scientists, such as Dr Jeff Parr of Southern Cross University, point out that in addition to the wide range of human uses, bamboo may also provide a variety of potential ecosystem services, including erosion control. Bamboo has an extensive fibrous root system, and new culms are produced from underground rhizomes. This means that harvesting can occur without significant disturbance to the ground or even the dense leaf litter, which also contributes to protecting the soil from wind and rain events. The thick leaf litter produced by bamboo also collects and conserves moisture. Bamboo has been extensively used in South America, China and India for remediation and protection of degraded landscapes.

Dr Parr has been investigating the potential for soil organic carbon sequestration by bamboo leaf litter in collaboration with researchers from the Fujian Academy of Forestry Sciences in south-east China.

‘All bamboo leaves a prolific amount of leaf litter on the ground, and we’ve been looking at the leaf litter because the rest is often harvested,’ says Dr Parr. He explains that the Chinese are interested in this research.

|

|

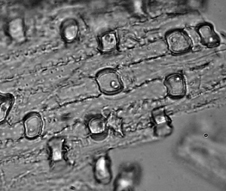

Bamboo phytoliths (under magnification). Credit: Jeff Parr

|

‘A lot of bamboo in China is economic bamboo that is used for the production of lots of things, from flooring to clothing. They are interested in the sustainable harvest and use of bamboo, and at the same time are interested in what it’s doing in the way of locking up carbon. They’re interested in carbon trading,’ he says.

According to Dr Parr, leaf litter is often overlooked in carbon inventories. This is significant, because he says that it is mainly the phytoliths, or plantstones, produced in the epidermal cells of a plant’s leaf, sheath and stem that are good at occluding carbon. Phytoliths form as microscopic silica grains in the leaves and stems of many plant species (see Ecos Issue 145). They are particularly prolific in grasses such as bamboo species, and become incorporated into the soil matrix during decomposition of leaf matter. In a paper published in Global Change Biology, Parr and his co-researchers state that ‘relative to the other soil organic carbon fractions that decompose over a much shorter time scale, the carbon occluded in phytoliths is highly resistant against decomposition’.4

|

Australia has three native species of bamboo, all of which grow in northern Australia. One of these is Bambusa arnhemica, which is found in the top end of the Northern Territory. Its edible shoots are harvested in the wild under a permit system. |

Between 1996 and 2002, an event occurred that was of intense interest to botanists and bamboo afficionados. A wave of synchronous flowering occurred, with a succession of stands flowering in successive years. Although some bamboo species flower annually, many do not flower at all until the end of their lives. Some of these ‘semelparous’ species flower and die synchronously, and in spatio-temporal waves, such as happened with Bambusa arnhemica. How this works remains a biological mystery. |

More information |

Franklin DC (2004). Synchrony and asynchrony: observations and hypotheses for the flowering wave in a long-lived semelparous bamboo. Journal of Biogeography 31, 773–786. |

|

Bamboo has the ability to take up more water and nitrogen than it needs for optimal growth, and 80% of its dense, shallow root system can be found at a depth of 0–40 cm. An effluent reuse scheme in Bangalow in northern NSW is designed to take advantage of these features. |

A 4.5 hectare site adjacent to the Bangalow sewage treatment Plant has been planted with a number of different species of non-invasive clumping-style bamboos, and is being irrigated with treated effluent from the plant. |

‘The primary function of the bamboo is to uptake the effluent so we don’t have to discharge it into the local creek,’ explains Michael Bingham of Byron Shire Council. The scheme has been a success in those terms, but the secondary objective of finding a market for the bamboo has not been met, with the council unable to find anyone to harvest and sell the bamboo. |

More information |

1 Midmore DJ (2009). Bamboo in the global and Australian contexts. Proceedings of a workshop held in Los Banos, the Philippines, 22–23 November 2006. Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research. http://aciar.gov.au/publication/PR129

2 Meyer D (2009). Demand for bamboo grows as wood substitute and food, China Daily, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/bizchina/2009-11/16/content_8975436.htm

3 Traynor M and Midmore D (2009). Cultivated bamboo in the Northern Territory of Australia. Proceedings of a workshop held in Los Banos, the Philippines, 22–23 November 2006. Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research. http://aciar.gov.au/publication/PR129

4 Parr J, Leigh S, Chen B, Yew G and Zheng W (2009). Carbon bio-sequestration within the phytoliths of economic bamboo species. Global Change Biology, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.02118.x